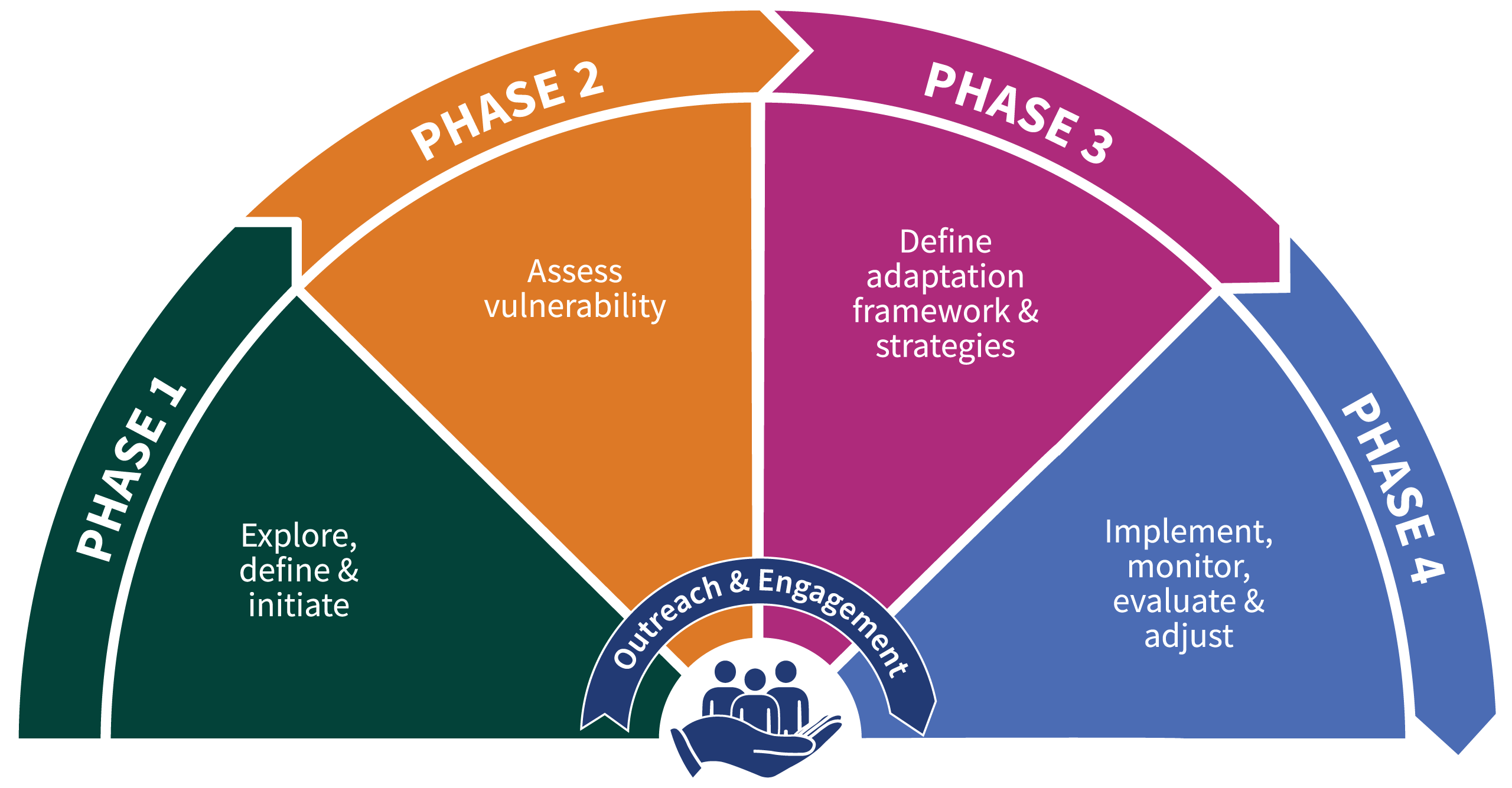

The 2020 California Adaptation Planning Guide 2.0 (APG) sets forth a detailed, four-phase process to help local governments, regional planning agencies, and tribal governments as they develop and integrate climate adaptation and resilience strategies. The Regional Resilience Framework (RRF) compliments the California Adaptation Planning Guide and provides localized guidance for SANDAG member agencies to help them build resilience to climate change hazards such as sea-level rise, extreme heat, wildfires, rain events, and other climate-related issues. Our Regional Climate Adaptation Planning Guide (below) is part of the RRF and is our localized version of the California APG.

At the beginning of the framework planning process, member agencies were surveyed and interviewed about the progress of their adaptation planning. Because there are numerous and often overlapping plans that can include adaptation components—such as stand-alone Climate Action Plans and/or Climate Adaptation Plans, Hazard Mitigation Plan updates, and General Plan updates—most jurisdictions found themselves in many different phases at once. Since hazards such as sea-level rise and wildfire have been at the forefront of regional planning for many years, jurisdictions are often in the later stages of addressing these hazards. In regard to emerging hazards such as extreme heat, jurisdictions are often in earlier stages.

To help member agencies understand their status in adaptation planning and what to do next, we’ve outlined each phase and its corollary steps below. The “Start Here” guide at the beginning of each phase includes considerations for each hazard. If your situation matches the status description in the “Start Here” guide, you’ve found the appropriate place to begin.

These assessments can be repeated over time as plans are adopted, implemented, and updated.

Funding for this project was provided by a grant funded through Senate Bill 1, the Road Repair and Accountability Act of 2017, Caltrans Formula Funds Work Element 320170 and 3201701.

Regional adaptation planning consists of four phases. Assessments can be repeated over time as plans are adopted, implemented, and updated.